Making sense of town council financial reports

- Feb 13, 2020

- 8 min read

Updated: Feb 14, 2020

Financial statements from 2015 to 2018 show most town councils to be in deficit if they had not received government grants to offset their spending

Pasir Ris-Punggol residents may want to read this. Residents there received the least in maintenance services per dollar of conservancy charge its town council collected over the past five years

ILLUSTRATION: LIANG LEI

By Daryl Choo

Never mind that residents in housing estates pay service and conservancy charges (S&CC), the bet is that not many look at their town council’s financial reports to see how well their money is being used. Beyond reacting to announcements about town council improvements or changes to S&CC charges, the assumption is that all will be well under the administration of elected MPs.

The dispute between Aljunied-Hougang Town Council (the entity) and the Workers’ Party MPs and volunteers who run the town council, now heading to the appeal courts, has brought financial prudence under the spotlight.

So are the 16 town councils really giving residents bang for their buck? Can town councils still function if Government grants are not available or if residents decide to withhold payments? That depends on how each town council operates.

Looking at financial statements from 2015 to 2018, most town councils would be in deficit if they did not receive government grants to offset their spending.

After taking the average of each town council’s operational deficit over this period of four financial years, ending in March, these deficits run in the range of $1.1 million (Marsiling-Yew Tee) to $6.7 million (Tanjong Pagar) a year.

Not counting government grants, town councils have only one main source of income — S&CC charges paid by Housing and Development Board (HDB) residents and by tenants of shops, offices and market stalls within the town estates.

Town councils must then set aside at least 26 per cent of these charges into their sinking funds for use in long-term projects and, from 2017, at least 14 per cent for lift replacements. If a town council’s day-to-day spending exceeds the remainder of its earnings after these transfers, then it is considered to be in operational deficit.

Only three town councils were not in operational deficit over the same period. Sembawang Town Council had $382,000, Holland-Bukit Panjang Town Council had $691,000 while Pasir Ris-Punggol Town Council (PRPTC) chalked up $2.7 million in operational surpluses each year on average.

When the grants are factored in, all town councils went into positive territory, with operating surpluses ranging from $1.6 million (Marsiling-Yew Tee Town Council) to $9.5 million (PRPTC) a year on average within the same period.

Town councils receive government grants each year based on the number of lifts, HDB flat units and flat types in each estate. Generally, town councils of larger constituencies with more units get bigger grants, like PRPTC, which was awarded $22.3 million in total grants in 2018.

No household unit numbers are available but the town council’s reach spans housing estates in Pasir Ris, much of Punggol and Sengkang Central.

The smaller East Coast-Fengshan town council received $9.0 million that year.

In 2014, government grants were withheld from AHTC (which was then called the Aljunied-Hougang-Punggol East Town Council) after the Auditor-General’s Office unearthed accounting and governance lapses in AHTC.

The grants were returned in 2016, a little more than a year after the audit had concluded, when the town council eventually accepted conditions set by the Ministry of National Development (MND) to install safeguards to protect the council’s public funds. The withheld grants had accumulated to two years worth of $12.9 million by that time.

Without grants, town councils would be hard put to balance their books and would be forced to raise other charges to meet expenditure. Improvement works will also be put on the backburner as current maintenance of the estate will take priority.

There is another source of funds, the Community Improvements Projects Committee fund which led to a recent public spat between Workers’ Party (WP) chief Pritam Singh and People’s Association (PA) grassroots adviser Chua Eng Leong who oversees the approval committee parked under the National Development ministry. You can read our story here.

RELATED STORY: CIPC funds: Which town council got how much

Besides meeting daily and short-term needs, are town council finances healthy enough to fund big projects, such as re-painting of blocks and replacement of water pumps?

Based on their average expenditure on large projects in the past four financial years, some town councils, such as AHTC, have enough reserves to last two years, while others, like Jalan Besar Town Council, have enough set aside for more than 17 years.

ARE RESIDENTS OVERPAYING?

But first, are residents getting a bang for their buck in S&CC payments?

One way to find out is to compare the town councils’ total S&CC income with their operational expenditure. It shows how much, for every dollar of S&CC fees residents and stall tenants pay, they receive in day-to-day cleaning and maintenance services.

By this measurement, Tanjong Pagar residents received the most in services for the amount of S&CC they pay — 93 cents worth of services per dollar of S&CC they pay.

Residents living in the Pasir Ris-Punggol estates received 75 cents of services per dollar, the lowest among all the towns.

Even though different town councils set their S&CC rates independently, the rates did not differ by much. Tanjong Pagar Town Council charges $45 for a standard three-room flat while PRPTC charged $44.50 a month. The cheapest was Sembawang Town Council at $43.50 while the most expensive was $47.50 in the Jurong-Clementi and Ang Mo Kio estates.

On average, conservancy charges collected by town councils were about 22 per cent higher than what was spent on short-term maintenance needs like estate cleaning and repairs, our calculations showed.

This may not mean that residents are overpaying as the town councils must also put aside funds for larger long-term projects, which is why town councils mostly fall in deficit before any government grants.

Amount each town council spends on cleaning and maintenance services per dollar of service and conservancy charge paid by residents and stall tenants. SOURCE: TOWN COUNCIL FINANCIAL REPORTS

A more accurate gauge of calculating whether a resident is overpaying would be to calculate its income, spending and surpluses for every HDB household in each estate.

But HDB unit numbers under each town council’s care was only reported in the town council reports of East Coast-Fengshan and Bishan-Toa Payoh. Despite multiple emails and phone calls, we managed to obtain these statistics for only three other town councils – Masiling-Yew Tee, Sembawang and West Coast. MND said it was unable to provide the specific data.

Taking into consideration these numbers, the amount these town councils spent on each HDB household ranged from $43 (Sembawang) to $52 (East Coast-Fengshan), which are similar to how much they would have collected in conservancy charges from a family living in a three-room flat. This means that those living in one- and two-room flats would stand to benefit more from the town council’s spending than what they pay in charges.

WITHOUT GRANTS, TOWN COUNCILS ARE REGULARLY IN DEFICIT

Another way to judge whether residents get the most value out of their S&CC payments is to examine how much excess, or surplus, their town council collect from S&CC payments and other income like car park fines and late payment fees.

As it turns out, all but three town councils regularly spent more on short-term maintenance services than they collected, after making the mandatory transfers to their funds for long-term projects.

PRPTC, which spent the least on these short-term operations, chalked up the highest operational surpluses both before and after government grants of $2.7 million and $9.7 million a year, from 2015 to 2018.

Part of the reason for the high surpluses could be due to the large number of HDB residents in the town, who had contributed to an S&CC income of $82.7 million annually, allowing the town council to benefit from economies of scale.

Besides Ang Mo Kio Town Council ($70.9 million), other town councils collected about half that amount in S&CC income.

Operational surpluses and deficits of town councils, before (grey) and after government grants, averaged from 2015 to 2018. SOURCE: TOWN COUNCIL FINANCIAL REPORTS

PRPTC manages the Punggol East single-member constituency and Pasir Ris-Punggol group representation constituency, which is the largest constituency accounting for 242,000 electors.

Town councils are also allowed to invest a portion of their reserves, although any interest or investment gains must return to the respective funds it came from, so town councils cannot use gains from their sinking fund investments to fund their short-term operations.

HOW STRONG ARE TOWN COUNCIL RESERVES?

If town councils were to stop collecting conservancy charges or receiving government grants, their long-term reserves would be able to pay for at least two years of large-scale projects for the town, according to financial statements.

Comparing sinking fund balances and expenditure showed AHTC having the lowest long-term financial viability. Based on its average sinking fund expenditure of $24.1 million from 2015 to 2018, its average sinking fund balance of $53.4 million would only last the town council 2.2 years without top-ups. Other town councils with less than three years worth of sinking fund expenditure in its fund balance were PRPTC, HBPTC and Tampines Town Council.

In comparison, Jalan Besar Town Council had an average sinking fund expenditure of $9.5 million, which means its average sinking fund balance of $164.7 million would last it 17.3 years of long-term spending.

Number of years each town council’s sinking fund can sustain their spending on large-scale projects. SOURCE: TOWN COUNCIL FINANCIAL REPORTS

Another method of assessing a town council’s financial strength is to look at its debt ratio, similar to how investors assess a company’s financial standing. This involves looking at the ratio of its total liabilities and total assets to examine the town councils’ financial risk — a higher ratio represents a higher dependence on debts.

Two town councils — Tampines and Marine Parade — were found to have higher debt ratios in the financial year ended 2018 compared to 2016. In 2018, Tampines Town Council and Marine Parade Town Council had 20 per cent and 11 per cent of their assets provided by debt respectively.

The debt here refers to current liabilities due to be paid within a year such as S&CC fees received in advance. Financial reports did not flag any long-term liabilities in the town councils’ statements.

Town councils’ efficiency ratios charted against their long-term viability metrics. The higher a town council is on the vertical axis, the more they collect in excess of what they spend operationally. The further a town council is to the right, the longer their long-term reserves can sustain their operations. SOURCE: TOWN COUNCIL FINANCIAL REPORTS

GOVERNING TOWN COUNCIL FINANCES

In 2017, MND announced new rules that town councils have to abide by which will take effect from April this year. This was aimed at strengthening the corporate governance of town councils.

These rules include risk management controls to track its financial risks and measures to guard against them, which they have to publish in their annual reports. Town councils would also have to conduct more regular reviews of their financial management, which includes their financial budgeting, reporting and fund investment reviews.

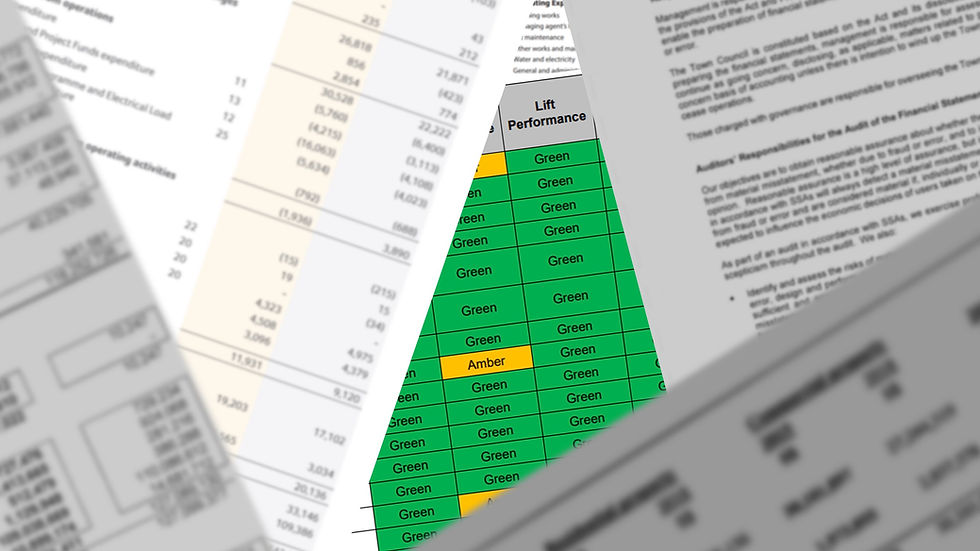

Currently, town councils are scored on their town management in an annual report published on MND’s website. They are also audited every year by independent auditing firms.

From 2015 to 2018, only AHTC received “red” bandings in the management reports, representing that the town council lacked in certain areas of management.

It received a “red” banding for 2015 for having a considerable number of households who had overdue S&CC payments. Audit firm KPMG in 2017 reported that the town council has since resolved this.

AHTC again received a “red” banding in 2016, this time for issues related to corporate governance. This was due to its “late quarterly transfer to the sinking fund”, “waiver of quotation that was not in accordance with requirements under the Town Council Financial Rules” and its “fixed assets count report not (being) certified by the Town Council in accordance with requirements”.

AHTC reported in Feb 2018 that it had fully resolved all issues previously flagged up by KPMG. In the 2018 management report, AHTC submitted clean financial accounts for the first time since 2011. It scored “green” in corporate governance and received two “ambers” in estate management and cleanliness.

During the release of the report, MND said it had asked AHTC why it did not require Workers’ Party MPs Sylvia Lim and Low Thia Khiang to discharge themselves from the town council’s financial matters.

This came after a High Court verdict in October last year which found that both MPs had acted dishonestly, which the duo is challenging. Parliament also approved a motion calling for their recusal.

In January, MND issued an order under the Town Council Act to force AHTC to restrict the powers of Ms Lim and Mr Low to make certain financial decisions. The town council complied.

Town councils release their financial data to the public every year in the spirit of transparency so that their residents can keep them accountable. While the new MND governance rules will help ensure stricter compliance with town council governance standards, it will still be up to the residents to decide if they believe they are fairly charged and whether they agree with how their town council spend their public monies.

Comments