Top billing: The MPs who put legislation in Parliament under the microscope

- Nov 7, 2019

- 9 min read

Updated: Feb 11, 2020

Forty-five new laws have been created in this term of Parliament

Notable bills that were introduced and passed in 2019 include the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act and changes to the Penal Code

By Sean Lim

ILLUSTRATION: JOIE CHEO

If you’re thinking of forming a debating team, try recruiting Nee Soon GRC MP Louis Ng. He takes the top prize as a debater, speaking on a total of 122 Bills in Parliament.

You’d be surprised at his range. And no, they aren’t always about animals.

This 13th term of Parliament hasn’t ended yet, but it is proving to be an extremely busy one. As of October 2019, 163 Bills have been approved, including 45 new ones. In contrast, the 12th Parliament handled 141 Bills in all and introduced 34 new ones. One was actually introduced in the last Parliament and amended in the current one – the Protection against Online Harassment Act. (The figures here exclude Supply Bills which are introduced and passed every year after the Committee of Supply debates)

Approving legislation is the focus of Parliamentary work. Members of Parliament scrutinise legislation that the Government proposes, to make sure they are really necessary, workable and fair to citizens. Because once a Bill is given the green light, it’s law and can’t be changed unless Parliament sits to amend it.

A Bill may be a brand new law or an amendment to existing laws. But even after it has made its way through Parliament, it needs to be scrutinised by the Presidential Council for Minority Rights. It will then report to the Speaker of Parliament if there are clauses in the Bill which discriminates against any race or religion. Once approved, the President of Singapore will give her assent and it becomes law when gazetted. There has been no record of any law which got the thumbs down from the council.

Also, the words in the law aren’t the full picture as details would be fleshed out in what is known as subsidiary legislation, as is the case for the Protection against Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act.

Here is the breakdown on Bills introduced by the different ministries and the number of MPs who spoke on them in this term of Parliament as of September 2019.

TABLE: SEAN LIM/ SOURCE: PARLIAMENT OF SINGAPORE

Law and order Bills accounted for 35 per cent of new laws passed. They come at a time of heightened security concerns over foreign influence, the terrorism threat and the need to maintain social cohesion. Many were conceived because of the experience of other countries which are becoming increasingly polarised by political ideologies, socio-economic class, or race and religion.

But the biggest change has less to do with the above threats than a need to update the law to fit in with changing social mores on what is a lesser or bigger crime, the extent of protection for the vulnerable in society and whether penalties are commensurate with crimes committed.

This involved changes to the Penal Code, the result of a two-year review of the justice system. They took the form of the Criminal Law Reform Bill in May this year, with a significant portion devoted to increased protection for the vulnerable and the young.

Conduct such as sexual communication with those under 18, like showing them a sexual image and performing sexual activities in their presence, are outlawed. Those who abuse vulnerable victims, such as disabled people or domestic foreign workers, or failed to protect them, can be jailed up to 20 years, fined and/or caned.

Volunteer organisations lobbying against the criminalisation of attempted suicide and women’s groups who wanted non-consensual sex between husband and wife to be made a crime of marital rape also got their wish. Overall, 19 MPs jumped into the debate.

Like the Criminal Law Reform Bill, the Administration of Justice (Protection) Bill updates and also puts together all the disparate laws that have to do with the court process and the functioning of the judiciary, including specific penalties. Twenty MPs spoke and the debate on 15 August 2016 took close to seven hours.

Two other big changes come in the form of the Public Order and Safety (Special Powers) Bill (POSSPA), which adds to the existing Public Order Act. POSSPA grants the Police new powers to act during major security incidents, including the authority to curb public communications in affected areas. That means you can’t be taking pictures in the area where an attack took place or risk being jailed for up to two years, fined $20,000 or both. This Bill was introduced in response to attacks in other countries, where ongoing police operations were compromised by live footage.

A more well-known acronym is POFMA or Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act, because it covers all manner of online speech and became law after an almost six-month review by a Parliamentary Select Committee. It marked the first time in 23 years that a parliamentary select committee was convened to elicit feedback on a policy. The last time was in 1996 when a committee was formed to examine healthcare subsidies of government polyclinics and public hospitals.

The Pofma debate on 7 and 8 May 2019 involved 39 MPs over 14 hours, with questions centred on the power given to ministers to decide on the veracity of statements, action to be taken and the recourse available to those who think they have been wrongly accused.

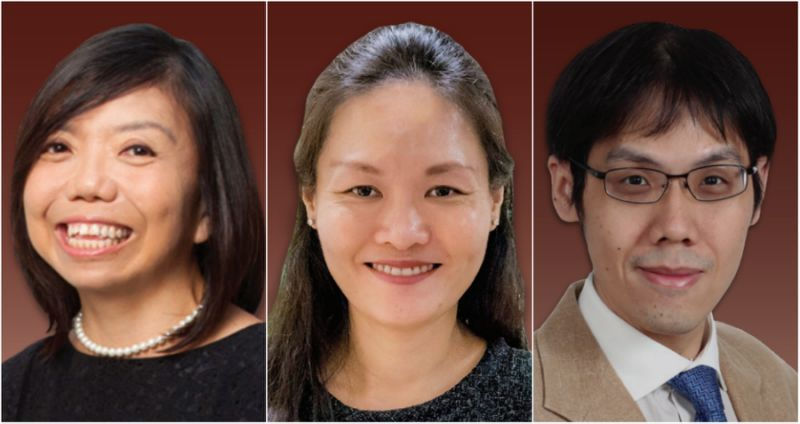

During the Pofma debate, three Nominated MPs (NMPs) – Anthea Ong, Walter Theseira and Irene Quay – proposed amendments to the Bill. Among other proposals, they wanted a requirement that the Government explain its decisions when exercising the law, and also for the appeals processes against the Government’s directions to be expedited.

Nominated Members of Parliament (from left) Anthea Ong, Irene Quay, and Walter Theseira proposed amendments to the Pofma Bill. PHOTOS: PARLIAMENT OF SINGAPORE

Their move was unusual for a few reasons. These amendments were formally proposed when a Committee of the Whole House (consisting of all MPs) was formed to scrutinise the details of the Bill. While changing certain clauses of the Bill is technically allowed at this stage of the law-making process, it seldom happens. So for most Bills, this stage can be settled within a minute or two but here, the deliberations lasted close to 15 minutes.

In any case, the NMPs’ proposal didn’t go through. The Workers’ Party (WP) MPs abstained while the People’s Action Party (PAP) MPs rejected it.

One key argument for Pofma’s executive fiat is the need for speed as controversial or sensational statements are spread faster online. This same argument has also been made for changes to the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act, which was passed by Parliament on 7 October 2019. The Government can now issue an order immediately to prevent an errant preacher from stirring animosity between religious groups or promote a political cause under the guise of religion, unlike the 14 days notice previously.

Other notable Bills include those intended to keep up with technological changes, such as the setting up of Government Technological Agency which provides the government’s digital services to the public and to tackle cyber-security issues. The Public Sector (Governance) Bill also meant civil servants can’t share data between public sector agencies frivolously unless they have a purpose as specified in the rule book.

An added layer of data protection: the Cybersecurity Act demands that owners of critical computer systems, such as those dealing with defence and public health, report breaches to the Commissioner of Cybersecurity and to follow more rules which include conducting of audits and risk assessments.

Another that might please Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg, who berated world leaders for environmental inaction: Singapore has the Carbon Pricing Act, passed on 20 March 2018, which imposes a tax on large emitters of greenhouse gases, such as power stations.

CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENTS

As the mother of all laws in the country, the Constitution of Singapore lays down Singapore’s political framework and contains provisions including those relating to sovereignty, fundamental liberties, citizenship and the public sector. Unlike normal Bills which require a simple majority from all MPs, any constitutional amendments need the consent of two-thirds of MPs (excluding Nominated MPs). These are the amendments made to the Constitution during this term of Parliament:

Changes to the Elected Presidency

Under the updated Constitution, a presidential election will be reserved for a particular racial group if no one from that group has been president for five continuous terms. The Government will start counting from the term of Dr Wee Kim Wee, who was the first president to be vested with the powers of an Elected President. All six elected MPs from the WP opposed the amendments, when they had to vote on it on 9 November 2016. The Bill was approved and it became the Malay community’s turn to have a president from their race the next year. Madam Halimah Yacob was then elected president.

Changes to the Non-constituency MP scheme

Besides amending the elected presidency scheme, the Government in November 2016 also made changes to the Non-constituency MP (NCMP) scheme. Previously, the Constitution only provided for a maximum of nine NCMPs in the House. The number has been increased to 12. Also, NCMPs will now have the same voting rights as elected MPs. Before this change was mooted, NCMPs can vote on all Bills except on constitutional changes, supply and money Bills, votes of no confidence in the Government and removing a President from office. At the end of the day, the six elected MPs from the WP voted against the constitutional amendments, while the remaining 77 PAP MPs voted in support.

The WP disagreed with the principle behind the NCMP scheme because they claimed it did not make parliamentary debates more robust, despite having three NCMPs in the House.

Work in progress: New Appellate Division for the High Court

On 7 October 2019, the Ministry of Law tabled amendments to the Constitution to restructure the Supreme Court by forming a new Appellate Division in the High Court to hear civil appeals not allocated to the Court of Appeal. This is to reduce the burden of appeal caseload by the apex court. More details will be fleshed out during the Second Reading in another parliamentary sitting.

Below are the top three Bills which got MPs excited, based on the number of MPs who spoke up and the duration of the debate. They are (in descending order):

TABLE: SEAN LIM/ SOURCE: PARLIAMENT OF SINGAPORE

AMENDING EXISTING LAWS

Besides the 45 new Bills passed in this term of Parliament so far, there were another 118 Bills to amend existing laws.

Most are to update legislation on law and order, such as the Road Traffic (Amendment) Bill which stepped up the punishments for traffic offences, the Misuse of Drugs (Amendment) Bill where repeated drug abusers undergo rehabilitation instead of a jail term, and the Immigration (Amendment) Bill which empowers immigration officers to search individuals they suspect are carrying offensive weapons in the vicinity of a checkpoint, instead of just within authorised areas in the checkpoint.

Some don’t seem to excite MPs at all, such as the Bills below which got through the House without debate.

1. Pioneer Generation Fund (Amendment) Bill 2019

2. Customs (Amendment) Bill

3. Evidence (Amendment) Bill

4. Regulation of Imports and Exports (Amendment) Bill

5. Pioneer Generation Fund (Amendment) Bill 2016

6. Income Tax (Amendment) Bill 2016

7. Goods and Services Tax (Amendment) Bill 2016

A look at the Bills showed that they were technical in nature. There were mostly changes in numbers –such as increasing the top marginal tax rate by two per cent – under the Income Tax (Amendment) Bill 2016, while the Pioneer Generation Fund (Amendment) Bill 2019 was a modification to include the Merdeka Generation package – nothing out of the blue since it was already announced during the Budget statement earlier.

Evidence (Amendment) Bill, for example, is closely related to the Criminal Justice Reform Bill and any issues would have been raised by then.

There were 14 other Bills which only had one MP speaking on it before it was passed. Among the lone fighters, three of them belong to the specific Government Parliamentary Committee (GPCs) the PAP set up to scrutinise the ministry:

TABLE: SEAN LIM/ SOURCE: PARLIAMENT OF SINGAPORE

PERFORMANCES OF MPS DURING DEBATES

So how well did MPs discharge their roles as legislators?

We are wary about making judgment calls, but an idea of how hardworking an MP can be indicated by the number of times he or she has joined in a debate on legislation. Using this benchmark, Louis Ng of Nee Soon GRC spoke up the most, 122 of 168 Bills. He also took on five Bills solo, as indicated in the chart above. Here is the list of MPs (we’re only talking about backbenchers here because office-holders are the proposers of legislation) and how many times they spoke up on Bills.

1. Mr Louis Ng (PAP) — 122 times

2. Mr Gan Thiam Poh (PAP) & Er Dr Lee Bee Wah (PAP) — 43 times

3. Mr Dennis Tan (WP NCMP) — 38 times

4. Ms Joan Pereira (PAP) — 35 times

5. Mr Christopher de Souza (PAP) — 34 times

For a full list, read here. (LINK)

An MP wears many hats: technocrat, mobiliser, handyman who solves municipal issues for residents or even a vote-getter for their race. But he or she is first and foremost a parliamentarian, putting the P in MP. Turning up faithfully for those few sittings per month is one thing, but participating actively in the debates is another.

Former NMP Eugene Tan said MPs “need to come prepared and be committed to participate in the debates” with Speaker of Parliament Tan Chuan-Jin echoing the same sentiments. Eugene Tan also said they have a responsibility in representing their constituents.

How do Singaporeans know if their MPs are doing their job in Parliament? One way is through television news and newspapers, except that they would not be an accurate portrayal of an MP’s performance because not everything will be covered. This could be due to lack of space in print or bandwidth, or simply because what they said was deemed as not newsworthy.

Calls for a live telecast and streaming have been rejected repeatedly, and the public gallery in Parliament is usually devoid of spectators. This could point to a sense of apathy about what goes on in Parliament, as something that is not the individual’s business.

But it should be.

Comments